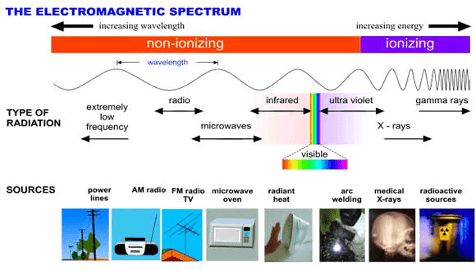

Where there is matter, there is radiation. It exists in both natural and manufactured sources, either as ionising radiation or non-ionising radiation. Understanding these differences is important for human health and safety in any circumstances.

Non-ionising radiation is largely harmless to health – at least in small doses. As defined by the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency

(ARPANSA), it ranges from extremely low frequency radiation to radiofrequency radiation. It is found in everyday life in radio, TV, mobile phones and other telecommunications, as well as in microwaves and ultraviolet radiation (UVR).

At the consumer level, the scientific consensus is that there is negligible risk from non-ionising radiation, although close proximity to high power output items, such as mobile phone towers presents some risk. It should be noted, however, that at the upper end of the spectrum, UVR becomes ionising and does present a huge risk for skin cancers – as we are well aware from the many years of SunSmart campaigns.

Ionising radiation, on the other hand, is radiation that has enough energy to alter the state of an object – in other words, to ionise it.

There are five common forms of ionising radiation: alpha, beta, and neutron radiation, gamma rays, and X-rays. While alpha, beta and neutron are particle types of radiation, meaning they have mass, gamma rays and X-rays are photons and have no mass, they just impart energy.

When ionising radiation interacts with living cells there is potential for harm. The risks might result from internal or external exposure to radiation. These risks will depend on the level of exposure and vary depending on the radiation type – for example, alpha radiation is not a health risk if external to the body, but certainly presents risk when a source of alpha radiation is inhaled or ingested.

In saying that, and to add context, we are all exposed to low levels of ionising radiation daily – in the forms of cosmic radiation, minerals and even food and water – which present minimal risk.

Exposure and safety measures

considering risk factors, therefore, it’s important to understand the difference between exposure to radiation occupationally, medically, as a member of the public, or our exposure to background radiation, which is the daily low-risk exposure that surrounds us.

Although dealt with separately, these exposures can be interconnected. For example, if you live or work close to a facility that operates equipment or devices that produce ionising radiation, or you are a visitor to that facility, it would be classed as public exposure. Those working with or close to that equipment are classified as having occupational exposure.

Examples of equipment or devices that produce ionising radiation and that are used in industrial settings may include:

- Airport baggage scanners

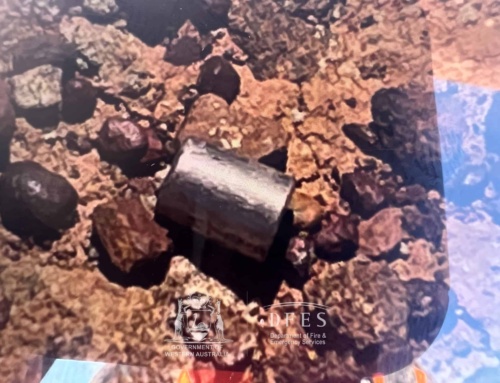

- Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (NORM), which emits ionising radiation through alpha, beta and gamma radiation

- Gauging devices found on pipework in processing plants and used to measure product characteristics, equipment levels, or product density

- X-ray equipment used in laboratories to characterise the elemental make-up of material, or to sort diamonds, or to image bone density and fat content in the meat industry

- Handheld X-ray analysers used in the field to ascertain the geochemical makeup of metal, or rock samples

- Non-destructive testing sources used to determine the quality of welds and metal integrity in the construction industry

The dos and don’ts of workplace safety

There are clear safety guidelines that organisations must follow to safeguard workers from radioactive materials. Federally, the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency regulates Commonwealth Entities. In Western Australia, the principal radiation regulator is the Radiological Council, which administers the Radiation Safety Act.

The Act requires that premises and radiation sources are registered and that individuals are licensed to work with radiation sources or under the supervision of a license holder. Organisations that work with radioactive substances are expected to have a Radiation Management Plan (RMP) or radiation safety manual that outlines how the business wants workers to manage radiation risks. This plan would be developed by technical experts – either internally or externally through a company like Radiation Services WA – and signed off by senior management.

Some companies do this well. For example, those working with Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials (NORM) will typically have a full time Radiation Safety Officer (RSO). Unfortunately, however, in most cases the person fulfilling the RSO role already has a full-time workload in the business – for example, an electrician or metallurgist. These part-time RSOs are still required to stay current with processes and requirements, yet with limited time to devote to this role, there is potential for the radiation management system to be suboptimal.

The quality of the RMP also needs to be considered. A good RMP, properly followed, is the best way to mitigate risks. But if it’s not properly followed, or if the plan is poor, the risks are likely to be greater.

Under the new Work Health and Safety Act in WA, which came into effect on 31 March 2022, it is a requirement for all businesses to provide a safe system of work for any worker, and that includes radiation safety. Making sure your workers are safeguarded against radiation risks should be a priority for any business using equipment that produces radiation. If you’d like a second opinion, contact RSWA to perform a review of your Radiation Management Plan.